STUDENTS ACCUSED OF SEXUAL ASSAULT ARE SUING COLLEGES

Nearly a

year after having what he claimed was consensual sex and she claimed was

assault, the two Aquinas College students were back together, this time

separated by a curtain.

For 50 minutes, they appeared in

front of a panel of employees of the college in Grand Rapids, Michigan. In

a 10-minute opening statement, the male student defended himself against

charges he had sexually assaulted the female student. The female student offered

no opening statement.

A few questions from the panel

later, the hearing was done. Six days later, the male student was expelled. Ten

months later, he filed a federal lawsuit. Several months after that, Aquinas

settled the lawsuit. Those involved are barred from talking about the case by

the agreement.

In suing, the Aquinas student

joined a growing tide of male students, accused of sexually assaulting fellow

students, who have lodged federal lawsuits against their schools, alleging

discrimination and violations of their due process rights.

Despite the continued heat of the

#MeToo movement that has brought down celebrities, politicians, business

leaders and religious leaders, the male students are finding success in the

court system.

In 2011, then-President Barack

Obama's administration urged universities to take more action

on sexual assault complaints.

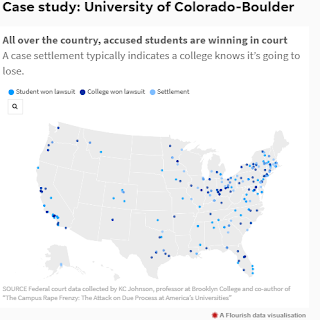

Since then, universities have

lost more decisions in these lawsuits than they have won, according to an

analysis of federal court filings. Most of the losses are judges deciding

against universities' motions to dismiss the cases.

"It's the end of the beginning," said Andrew Miltenberg, an

attorney with Nesenoff & Miltenberg who represents accused students,

including a trio suing Michigan State University. "We're seeing, for the

first time, in the last year or so, that courts are starting to

embrace the concept that there could be due process issues. Others are

not. We don't have a big jury case yet."

Several hundred cases have been

filed in the last eight years, with the pace picking up in recent years.

Now a case is filed every two weeks or so, experts said.

The

losses share a problem, said KC Johnson, a professor at Brooklyn College and

the co-author of "The Campus Rape Frenzy: The Attack on Due Process at

America’s Universities." Johnson has tracked the cases and provided the

Free Press with his database of cases and outcomes.

"One commonality is the lack

of cross-examination," he said. "Courts are saying each side should

have the opportunity to question each other."

Big universities

including the University of Southern California, Penn State University and

Ohio State have lost. Smaller schools, including Hofstra University,

Boston College and Claremont McKenna College have also been on the losing end

of decisions. Another group of schools, including Northwestern University,

Dartmouth College and Yale have settled lawsuits.

Universities, even when reaching

a settlement, aren't paying out large amounts of money to those accused

students who are suing them. They are often, instead, expunging findings,

giving clean transcripts or degrees, multiple lawyers said.

Many decisions are now being

appealed. At least one federal appeals circuit has already weighed in, with

others likely to do so in the coming months. Many believe a U.S.Supreme Court

case is the likely end point sometime in the next two to five years.

One of the people paying

attention to the court rulings is U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, who has proposed

new regulations for how colleges handle sexual assault. Among the regulations — live

hearings with cross-examinations.

The cases have often sent

the students back to the university with orders to redo the investigation under

procedures that correct due process flaws.

That's difficult

for sexual assault survivors, said Laura Dunn, a sexual assault survivor

and attorney.

"They have to go and sit

through it all again and relive the whole experience."

Miltenberg said he hasn't seen

any slowing of accusations.

"I still think there's a lot

of confusion out there on what needs to be done" by universities, he

said. And there was a need for courts to step in because "universities, on

their own, weren't going to get (to fair due process) on their own

In January 2016, an unnamed

female student filed a report with the Boulder Police Department that she

was sexually assaulted in July 2015 and that, in spring 2014,

Norris touched her genitals without her consent. That allegation was

shared with the school. Both the police and the school launched investigations.

Shortly after, a university

investigator emailed the female student: “No time limits on our side, so

if at any point you would like to speak with me about the incident, I am

available to meet or speak to you by phone," according to a federal lawsuit.

"The email further informed Jane Roe (the student) that her participation

in the process was optional and provided her with options for 'advocacy and

support.' "

Norris was notified a couple of

days later and given two days to find an adviser and set up a meeting with the

university investigator, according to the lawsuit. The lawsuit also claims he

was told that if he didn't respond, the university could continue the process

without him.

Throughout the process, the

lawsuit claims, the accuser was given leeway in deadlines and access to

information about the investigation, whereas Norris wasn't. He was allowed to

review the investigator's report, but only in the office and with a university

official sitting in. He couldn't make copies. Multiple witnesses supported his

version of events, the lawsuit states, but the witnesses were ignored. Norris

is represented by Miltenberg.

During the time of the

investigation, then-Vice President Joe Biden appeared on campus as

part of a week-long anti-sexual assault campaign. The lawsuit claims Biden's

appearance increased pressure on the university to find against male

students.

vice President Biden with University of

Colorado sophomore Emma Beach after speaking about sexual violence on campus as

part of the "It's On Us" campaign, April 8, 2016, at the University

of Colorado campus in Boulder, Colo. (Photo: Jeremy Papasso/Daily Camera via AP)

There was no hearing. The university's conduct

officer found the female student more credible and suspended Norris for 18

months, banning him from campus during that time. At the same time, a jury

acquitted Norris of all charges stemming from the complaint.

"CU Boulder’s investigation and

adjudication of Jane Roe’s allegations were tainted by gender bias resulting

from federal and local pressure to protect female victims of sexual violence,

and to reform CU Boulder’s policies to take a hard line against male students

accused of sexual misconduct," the lawsuit states. "As a result,

Plaintiff was deprived of a fair and impartial hearing with adequate due

process protections, as mandated by the United States Constitution."

A federal judge agreed there was enough

evidence to continue the case, defeating a motion to dismiss by the university.

The judge cited the growing case law around due process claims and said:

"The lack of a full hearing with cross-examination provides evidence

supporting a claim for a violation of his due process rights."

Growing number of

lawsuits

In 2011, the Obama administration issued what

became known as the "Dear Colleague" letter, demanding colleges up

their game when it came to sexual assault complaints. More sexual assault survivors

filed complaints with the federal government alleging their universities hadn't

handled their complaints properly. The federal government cracked down on

schools, including pre larry nassar scandal Michigan state, which the

government said had bad policies that contributed to a sexually hostile

environment.

Schools also switched to a single-investigator

method and trauma-informed processes. The single-investigator model works by

having a single university employee or outside expert interview the

accuser, the accused and any witnesses separately and then write up a

report. Both sides often have a chance to review the report, but can't ask each

other or witnesses questions.

But as the model of investigation changed,

complaints started to rise that universities had swung the pendulum too far and

were going into the process thinking the male students were guilty even before

gathering the evidence.

Since the "Dear

Colleague" letter, there have been more than 330 federal cases

in which some action has been taken. As of April 11, universities have lost

140 decisions, mostly motions to dismiss the lawsuit. They've won 126 times.

They have ended cases with confidential settlements 65 times.

Those numbers don't count the cases filed and

still working through the system. The estimate is one federal case is filed

every two weeks. That also doesn't count cases filed in state court systems.

"A

lot of these university policies are hard to defend," Johnson said.

"Universities ... are very slow to respond to adverse rulings and make

changes. That just leads to more cases

." Students walk down South

State Street on the University of Michigan central campus in Ann Arbor on

Wednesday, June 13, 2018. (Photo:

Kimberly P. Mitchell, Kimberly P. Mitchell, Detroit Fr)

Perhaps the most cited

recent ruling in court cases is a lawsuit stemming from the University of

Michigan and an appeals court ruling.

The case the appeals court was

considering centers on a sexual encounter at a fraternity party. The male

student was eventually thrown out of school.

The student then sued U-M,

alleging his due process rights weren't granted. A lower court ruled against

him, but he appealed.

His argument was that the

university already gave students accused of every other type of misconduct the

right to a hearing and cross-examination.

In its ruling, the court of

appeals bought that argument.

"If a public university has

to choose between competing narratives to resolve a case, the university must

give the accused student or his agent an opportunity to cross-examine the

accuser," the court wrote.

"Due process requires

cross-examination in circumstances like these because it is 'the greatest legal

engine ever invented' for uncovering the truth."

The impact of the cases

As a sexual assault

survivor-turned lawyer, Laura Dunn has seen the legal system from both

perspectives. She currently represents other sexual assault survivors,

including in lawsuits they file against universities.

Those cases can be tough to win

because civil rights violations have to show deliberate indifference. Educating

judges on those legal standards and how universities didn't meet them can be a

challenge.

On the other hand, she

says: "The staples of due process are very well understood."

But maybe not so by universities,

said Justin Dillon, a former federal prosecutor whose Washington, D.C.,

firm KaiserDillon represents accused students.

"The reason for the number

of cases and wins is sort of simple — schools rushed to implement a bunch of

questionable processes," he said.

It took a while for cases to

develop and work through the legal system, sort of a lagging indicator that

there were problems with how universities were handling the accusations.

Students getting expelled for

sexual assault accusations felt branded and that they would suffer reputation

harm that would last well past college. So when they saw flaws, they began to

sue and courts began to question procedures.

That's led to some good, Dunn

said, noting she's not a fan of the single-investigator model.

Universities are definitely aware of the court trend,

Miltenberg said. He is finding he can draft a complaint listing a number of

issues, present it to the university before filing and have universities

tell them to slow down the process and work with them to get a fair hearing.

No comments: